Pour voir la semaine du 5-11 mars, cliquez ici / To see the week of March 5-11, click here

Pour voir la semaine du 19-25 mars, cliquez ici / To see the week of March 19-25, click here

Mardi 18 mars 2025 / Tuesday 18 March 2025

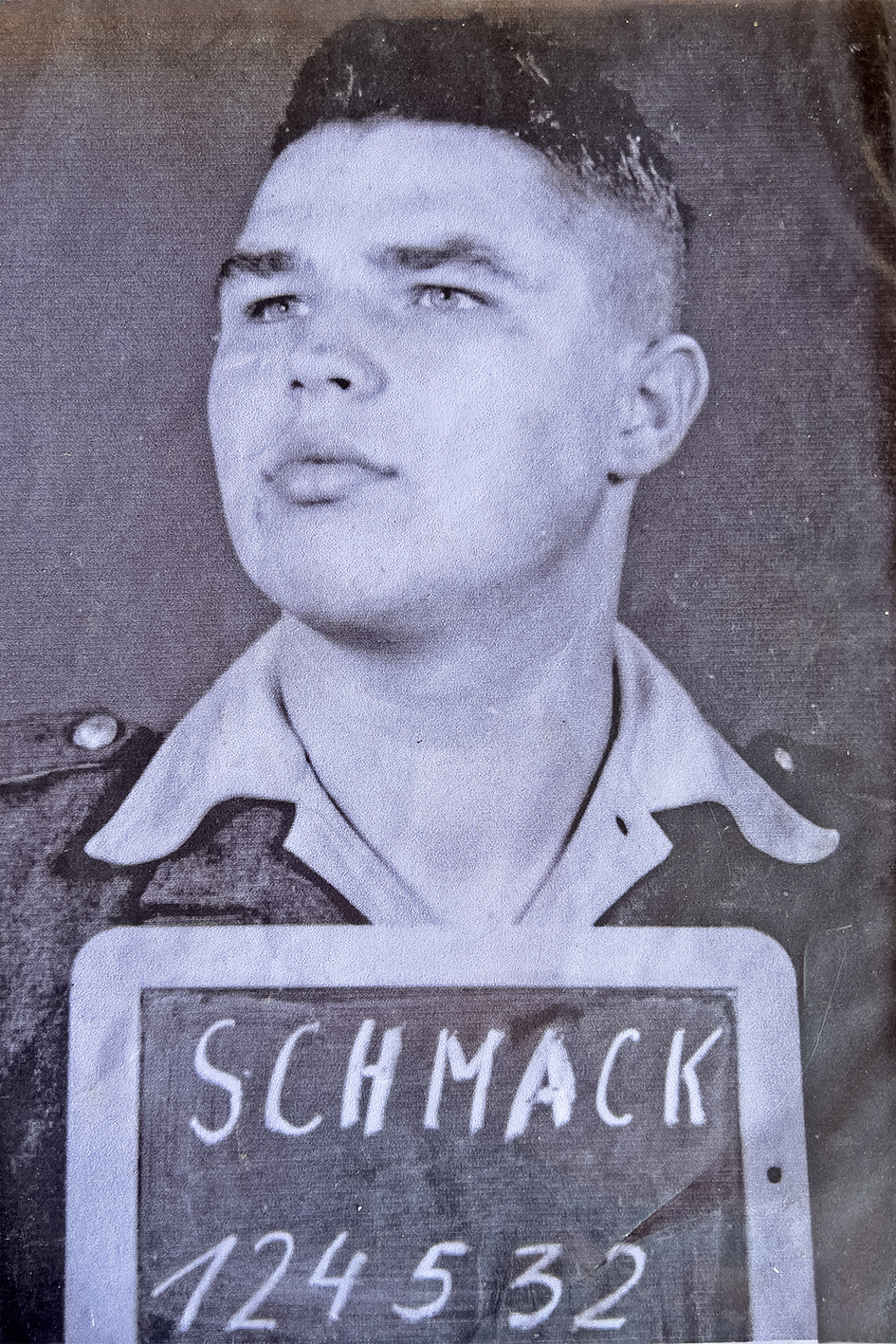

Fritz

L’une de ses six filles fait la lessive pour les plaisanciers qui accostent à Rikitea. On m’avait parlé de son père d’origine allemande. Curieux de savoir comment un Allemand a atterri au fin fond de la Polynésie, je rencontre Fritz, bientôt 85 ans. Heureux de pouvoir parler à quelqu’un dans sa langue natale, il ne se fait pas prier lorsque je lui demande s’il veut me raconter comment il est arrivé aux îles Gambier. Souffrant du dos et des séquelles d’un AVC, il se déplace péniblement avec des béquilles ou un déambulateur, mais passe le gros de sa journée allongé dans un lit spécialisé, ou assis pour regarder la télé. Il me reçoit assis à table, accoudé pour soulager son dos. Handicapé, mais il a toute sa tête et une sacrée mémoire ! / One of his six daughters does laundry for the boaters who dock at Rikitea. I’d heard about her father, who was said to be of German origin. Curious to know how a German ended up in the depths of Polynesia, I met Fritz, almost 85 years old. Happy to be able to speak to someone in his native language, he didn’t hesitate when I asked him if he wanted to tell me how he arrived in the Gambier Islands. Suffering from back pain and the after-effects of a stroke, he moves with difficulty using crutches or a walking frame, but spends most of his day lying in a specialized bed, or sitting up to watch TV. He receives me sitting at the table, leaning on his elbows to relieve his back. Disabled, but he has all his wits and a great memory!

« Je suis né à Essen le 22 octobre 1940 (SW : 6 ans avant moi, jour pour jour !). Mon premier souvenir d’enfance remonte à 1944, je devais avoir 3 ans et demi. La ville subissait un bombardement allié. Nous devions tous nous rendre dans un abri anti-aérien. Quand on est ressorti, il ne restait plus rien de notre maison : un tas de gravats et du feu, alors que les maisons à droite et à gauche n’avaient pas été touchées… / I was born in Essen on October 22, 1940 (SW: 6 years before me, to the day!). My first childhood memory goes back to 1944, when I must have been 3 and a half years old. The city was under Allied bombing. We all had to go to an air-raid shelter. When we came out, nothing remained of our house: a pile of rubble and fire, while the houses to the right and left had not been hit…

Ma mère et moi rejoignons alors ma sœur, membre de la BMD (SW : Bund Deutscher Mädel, les jeunesses hitlériennes pour filles) de 10 ans mon aînée, qui travaillait dans une ferme à Tüttlingen, dans le sud de l’Allemagne. Mon père continuait de travailler comme chef d’équipe dans une mine de charbon à Essen. / My mother and I then joined my sister, a member of the BMD (SW: Bund Deutscher Mädel, Hitler Youth for Girls) who was 10 years my senior and was working on a farm in Tüttlingen, in southern Germany. My father continued to work as a foreman in a coal mine in Essen.

Après-guerre / After the war

Ensuite, nous avons déménagé à Aspenstedt près de Halberstadt dans les montagnes du Harz. Mon père y travaillait comme cantonnier. Nous habitions une maison vieille de 100 ans, aux murs très épais. Quand j’avais 6 ans, mon père m’emmenait chaque matin à l’école avec un chariot tiré par notre grand chien, Bello. J’étais un très bon élève, le meilleur de la classe. / Then we moved to Aspenstedt near Halberstadt in the Harz mountains. My father worked there as a road mender. We lived in a 100-year-old house with very thick walls. When I was 6 years old, my father took me to school every morning in a wagon pulled by our big dog, Bello. I was a very good student, the best in the class.

Nous avions un grand jardin potager, dans lequel ma mère cultivait fruits et légumes, et dans un coin secret des plants de tabac pour mon père. Il suspendait les feuilles dans ma chambre afin de les faire sécher. Je me souviens encore de l’odeur ! Nous étions sous régime communiste et c’était totalement illégal ! On était en 1952 et tout était rationné. / We had a large vegetable garden, where my mother grew fruits and vegetables, and in a secret corner, tobacco plants for my father. He would hang the leaves in my room to dry. I still remember the smell! We were under a communist regime and it was completely illegal! It was 1952 and everything was rationed.

Avec trois de mes camarades on a volé quelques feuilles et on a secrètement fumé le calumet de la paix, comme Winnetou, le chef des Apaches, dans les romans de Karl May que nous avions tous lus. Mon père en a eu vent et ma interdit de fumer avec mes camarades. En revanche, il m’invita à fumer avec lui chaque dimanche après-midi. Il roulait son cigare et moi ma cigarette ! / Three of my friends and I stole some leaves and secretly smoked the peace pipe, like Winnetou, the Apache chief, in the Karl May novels we had all read. My father got wind of it and forbade me to smoke with my friends. However, he invited me to smoke with him every Sunday afternoon. He rolled his own cigar and I rolled my own cigarette!

Mon père était génial. Il n’était ni communiste, ni croyant. Il me disait ceci : « Il ne faut jamais croire. On sait, ou on ne sait pas ! » / My father was brilliant. He was neither a communist nor a believer. He used to tell me this: « You should never believe. You either know, or you don’t! »

Fuir la DDR / Escaping the DDR

Lorsque j’avais 14 ans, j’ai commencé le collège. Mais j’en avais vite assez, et j’ai décidé de fuir l’Allemagne de l’Est. J’ai franchi la frontière en me glissant sous les fils barbelés près du village de Schierke. (SW : C’était avant la fermeture définitive de 1961, assortie de champs de mines et de soldats armés qui tiraient sur chacun qui tentait de fuir la DDR). Puisque je suis encore mineur, on me place dans un camp pour réfugiés. Je travaille chez un agriculteur, dont le père, maire de la petite localité, me fournit des papiers d’identité. / When I was 14, I started secondary school. But I quickly grew tired of it, and decided to flee East Germany. I crossed the border by slipping under the barbed wire near the village of Schierke. (SW: This was before the final closure in 1961, accompanied by minefields and armed soldiers shooting anyone who tried to escape the DDR). Since I was still a minor, I was placed in a refugee camp. I worked for a farmer, whose father, the mayor of the small town, provided me with identity papers.

À l’âge de 16 ans, je me rends à Hambourg, où, étant toujours mineur, la police m’assigne à résidence dans une maison d’accueil pour jeunes dans la Thedestraße, non loin de la célèbre Reperbahn, le quartier rouge de la ville. Une grosse prostituée avec des seins énormes me proposer de me déniaiser. Intimidé, je prends mes jambes à mon cou ! Je travaille sur un chantier naval, où je ramasse les copeaux de bois que j’emmène chez les bouchers qui s’en servent pour fumer les saucisses. / At the age of 16, I went to Hamburg, where, still being a minor, the police placed me under house arrest in a youth shelter on Thedestraße, not far from the famous Reperbahn, the city’s red-light district. A large prostitute with enormous breasts invited me to be initiated. Intimidated, I ran away! I worked in a shipyard, where I collected wood shavings that I took to the butchers who used them to smoke sausages.

En quête d’aventure / In search of adventure

Mais je décide que je veux découvrir le monde. À 17 ans, je pars pour la France en autostop. À Paris, quelqu’un me parle de la Légion étrangère. Cela me semble être exactement ce qu’il me faut. Lorsque je me pointe à la caserne Guynemer à Strasbourg, j’ai 17 ans et 11 mois… un mois trop jeune pour me faire enrôler ! Je dis alors que je m’appelle Walter Steindorff – un ancien camarade de classe né en Prusse Orientale – mais que j’ai perdu mes papiers lors de ma fuite vers l’Ouest. Une semaine plus tard, on me fait venir chez le commandant. Celui-ci à commencé par me donner une gifle, puis il me traitait de menteur : « Je sais exactement qui tu es, Fritz Dieter Schmack ! » Et il donnait ma date et lieu de naissance, tout était exact… il savait tout ! À ce jour je ne sais toujours pas pourquoi et comment le 2ème bureau avait fait, mais cela partait de mes empreintes digitales. Bref, j’ai dû attendre d’avoir 18 ans et un jour, avant de pouvoir signer pour 5 ans auprès de la Légion. / But I decided I wanted to discover the world. At 17, I left for France by hitchhiking. In Paris, someone told me about the Foreign Legion. It seemed to me to be exactly what I needed. When I showed up at the Guynemer barracks in Strasbourg, I was 17 years and 11 months old… a month too young to enlist! I said my name was Walter Steindorff – a former classmate born in East Prussia – but that I had lost my papers when I fled to the West. A week later, I was summoned to the commandant. He started by slapping me, then called me a liar: “I know exactly who you are, Fritz Dieter Schmack!” And he gave my date and place of birth, everything was correct… he knew everything! To this day I still don’t know why or how the 2nd Bureau did it, but it was based on my fingerprints. In short, I had to wait until I was 18 years and one day old before I could sign a 5-year contract with the Legion.

On m’envoya d’abord à Aubagne, puis à Djelfa en Algérie pour 3 mois de formation. Dans la foulée, j’ai passé mes permis de conduire voiture et poids lourds. Ensuite, c’était la guerre contre le FLN au sein du 2ème Régiment Étranger de Cavalerie. Je faisais partie du 2ème escadron héliporté. Au cours d’une manœuvre, je tombe de 10 m de haut avec ma mitrailleuse et tout, et me fais un sérieux tassement de vertèbres. J’étais seul derrière un buisson et je souffrais le martyre. À 200 m devant moi, les rebelles du FLN et 200 m derrière moi mes camarades. Finalement, je m’en suis sorti. Quant aux gars du FLN, on ne faisait que rarement des prisonniers. Lorsqu’on en faisait, ils passaient au 2ème Bureau – c’était pire que la Gestapo ! / I was first sent to Aubagne, then to Djelfa in Algeria for 3 months of training. In the process, I passed my car and truck driving licenses. Then came the war against the FLN in the 2nd Foreign Cavalry Regiment. I was part of the 2nd helicopter squadron. During a maneuver, I fell from a height of 10 meters with my machine gun and all, and seriously crushed my vertebrae. I was alone behind a bush and I was suffering terribly. 200 meters in front of me were the FLN rebels and 200 meters behind me were my comrades. In the end, I made it. As for the FLN guys, we rarely took prisoners. When we did, they were taken to the 2nd Bureau – which was worse than the Gestapo!

En 1962, après la fin de la guerre d’Algérie, je suis stationné à Madagascar. Nous étions un médecin, un infirmier et un pharmacien, et dix légionnaires, chacun portant 40 kg de médicaments. Avec ça, on partait dans la brousse soigner les indigènes. Après, on a été rejoint par le 3ème REI, le plus décoré de toute la Légion. Notre devise : « LEGIO PATRIA NOSTRA », « La Légion est notre patrie », et on en était tous fiers, français ou pas. Je participe à la construction de la piste de Diego Garcia, responsable des deux tirs de mines quotidiens. / In 1962, after the end of the Algerian War, I was stationed in Madagascar. We were a doctor, a nurse, and a pharmacist, and ten legionnaires, each carrying 40 kg of medicine. With that, we went into the bush to treat the natives. Afterwards, we were joined by the 3rd REI, the most decorated of the entire Legion. Our motto: « LEGIO PATRIA NOSTRA, » « The Legion is our homeland, » and we were all proud of it, French or not. I participated in the construction of the Diego Garcia runway, responsible for the two daily mine blasts.

En 1964, devenu légionnaire 2ème classe, je suis affecté à Djibouti, où j’ai reçu une formation pour devenir caporal. De retour à Aubagne, je travaille au sein du service automobile, responsable de l’entretien et du dispatching. Vers 1967, je deviens sous-officier à Bonifacio. Je suis toujours parmi les meilleurs, fidèle à ce que m’avait inculqué mon père : « Quand on veut, on peut ! » / In 1964, having become a 2nd class legionnaire, I was posted to Djibouti, where I received training to become a corporal. Back in Aubagne, I worked in the automotive department, responsible for maintenance and dispatching. Around 1967, I became a non-commissioned officer in Bonifacio. I was still among the best, faithful to what my father had instilled in me: « Where there’s a will, there’s a way! »

Puis on me garde pour former les jeunes recrues. Mais il y avait de moins en moins d’aventuriers étrangers. En revanche, on recevait de jeunes délinquants français que l’on avait mis devant le choix : 3 ans de prison ou 5 ans de Légion. Ces garçons-là n’avaient pas le sens de l’honneur, comme nous, ni notre sens de camaraderie. C’était un sacré boulot d’en faire des légionnaires. On a dû les traiter à la dure. / Then they kept me to train the young recruits. But there were fewer and fewer foreign adventurers. On the other hand, we received young French delinquents who were given a choice: 3 years in prison or 5 years in the Legion. These boys didn’t have the sense of honor we did, nor our sense of camaraderie. It was a hell of a job turning them into legionnaires. We had to treat them harshly.

La Polynésie / Polynesia

En 1972, j’arrive à Tahiti. On m’affecte aux Gambier, où un régiment de légionnaires avait construit la piste de Totegegie. Je m’occupe de son entretien et de la station météo, jusqu’à ma retraite en 1974. Je n’avais alors que 34 ans ! Je prends 6 mois de vacances, mes premières depuis 1958, puis je retourne à Mangareva. Je voyageais gratis avec l’armée de l’air. Je m’installe dans une pension à Rikitéa. J’ai essayé deux ou trois filles, mais elles ne me convenaient pas. J’en avais eu pas mal d’autres partout où j’avais été affecté auparavant. Puis un soir, une jeune fille très belle s’est présentée devant ma chambre. Susanne, Tutana en mangarévien. Il faisait noir. À l’époque, il n’y avait pas encore d’électricité ici. Elle est venue dans mon lit, et ne l’a plus quitté jusqu’à son décès en 1999, morte en couches de notre cinquième fille. Elle avait déjà une fille quand nous nous sommes connus. Depuis sa mort, il n’y a plus eu d’autres femmes dans ma vie. / In 1972, I arrived in Tahiti. I was assigned to the Gambier Islands, where a regiment of legionnaires had built the Totegegie runway. I took care of its maintenance and the weather station until my retirement in 1974. I was only 34 years old at the time! I took 6 months of vacation, my first since 1958, then I returned to Mangareva. I traveled for free with the Air Force. I settled into a guesthouse in Rikitéa. I tried two or three girls, but they weren’t right for me. I’d had quite a few others everywhere I’d been posted before. Then one evening, a very beautiful young girl appeared in front of my room. Susanne, Tutana in Mangarevan. It was dark. At the time, there was no electricity here yet. She came into my bed and never left until her death in 1999, when she died giving birth to our fifth daughter. She already had a daughter when we met. Since her death, there have been no other women in my life.

Je savais tout faire : certains m’appelaient McGyver ! J’ai bâti le dispensaire ici et encore exercé plein d’autres métiers. Je suis vieux maintenant. Je n’aime pas dire que je suis malade, juste que j’ai des problèmes de santé. J’ai mal partout, mais je ne veux pas encore crever. Ma sœur est décédée à l’âge de 91 ans. J’entends bien la battre ! / I could do everything with my hands: some called me McGyver! I built the dispensary here and had many other jobs. I’m old now. I don’t like to say I’m sick, just that I have health problems. I’m in pain everywhere, but I don’t want to die yet. My sister died at the age of 91. I intend to beat her!

Mes leçons de vie ? 1. Ne pas croire. 2. Toujours être honnête. 3. Sans travail on n’arrive à rien. / My life lessons? 1. Don’t believe. 2. Always be honest. 3. Without work, you achieve nothing.

Tu reviendras me voir avant de partir ? Ça m’a fait plaisir de pouvoir parler allemand. Ça n’arrive pas très souvent. / Will you come back and see me before you leave? I was happy to be able to speak German. It doesn’t happen very often.

Je lui promets que je repasserai. / I promise that I will.

Lundi 17 mars 2025 / Monday 17 March 2025

Aujourd’hui, je n’ai pas fait grand-chose. Enfin, si : j’ai écrit le premier de mes quatre articles commandés par le journal « Ouest France », dans lequel je rappelle un peu l’histoire des Gambier et sa situation particulière si loin de tout. Sinon, quelques photos aériennes (drone) du voilier « Songster » au mouillage en baie de Rikitea. C’est ma maison pendant presque 4 semaines et j’y suis formidablement accueilli par Camila, Jurriaan et Chris ! / Today, I didn’t do much. Well, actually I did: I wrote the first of my four articles commissioned by the newspaper « Ouest France, » in which I briefly recall the history of the Gambier Islands and its particular location so far from everything. Otherwise, here are some aerial photos (drone) of the sailboat « Songster » at anchor in Rikitea Bay. It’s my home for almost 4 weeks and I’ve been wonderfully welcomed by Camila, Jurriaan, and Chris!

Dimanche 16 mars 2025 / Sunday 16 March 2025

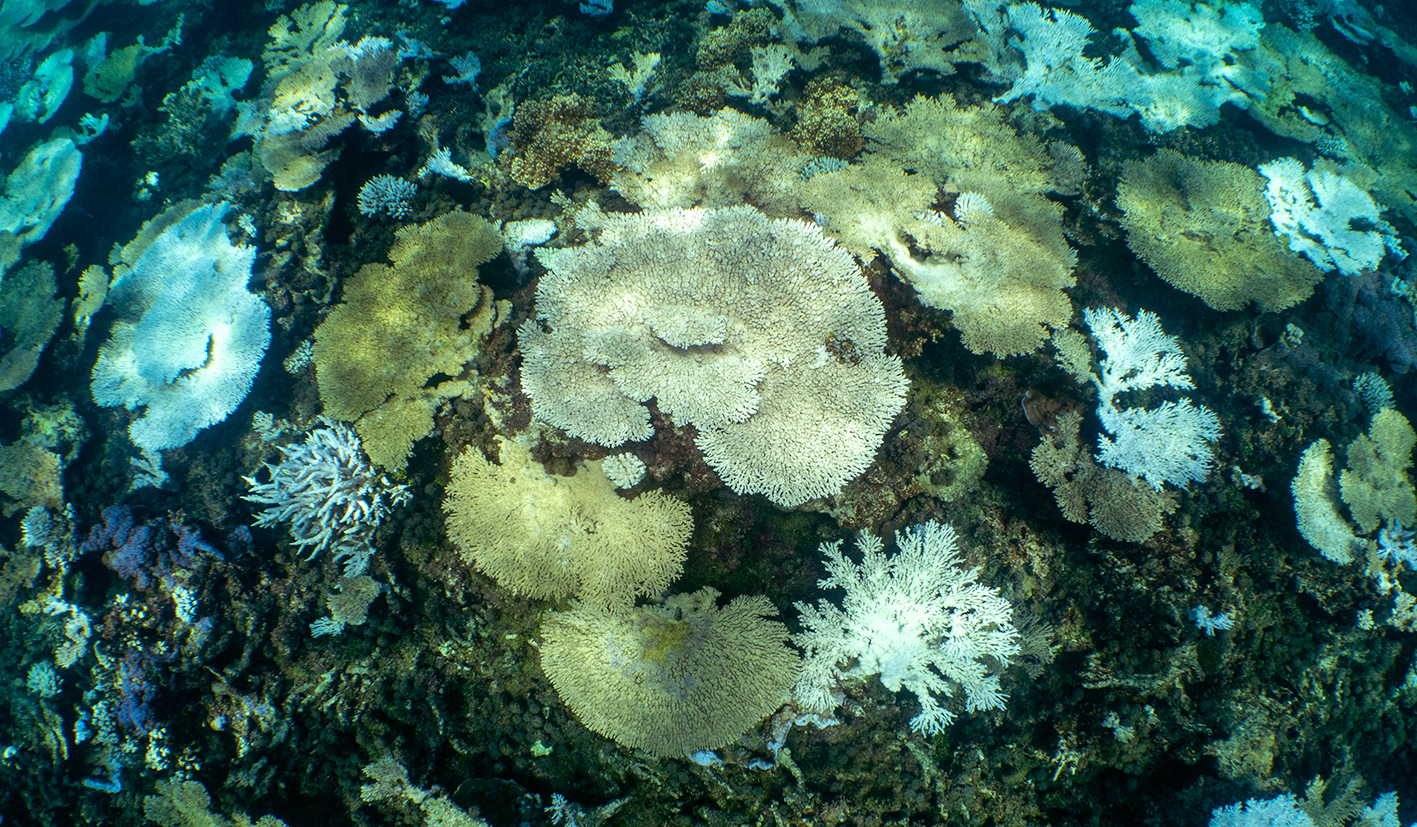

Une journée extraordinaire ! Pour la première fois, je trouve un récif assez riche devant l’île de Taravai, et, dans une eau… claire ! Énormément d’acropores, dont certaines colonies blanchies, mais dans l’ensemble ce récif a l’air d’être en bonne santé. Beaucoup de poissons aussi, dont des bancs de perroquets et de gros mérous. / An extraordinary day! For the first time, I find a fairly rich reef off Taravai Island, and in… clear water! A huge number of acropora, including some bleached colonies, but overall this reef seems to be in good health. Lots of fish too, including schools of parrotfish and large groupers.

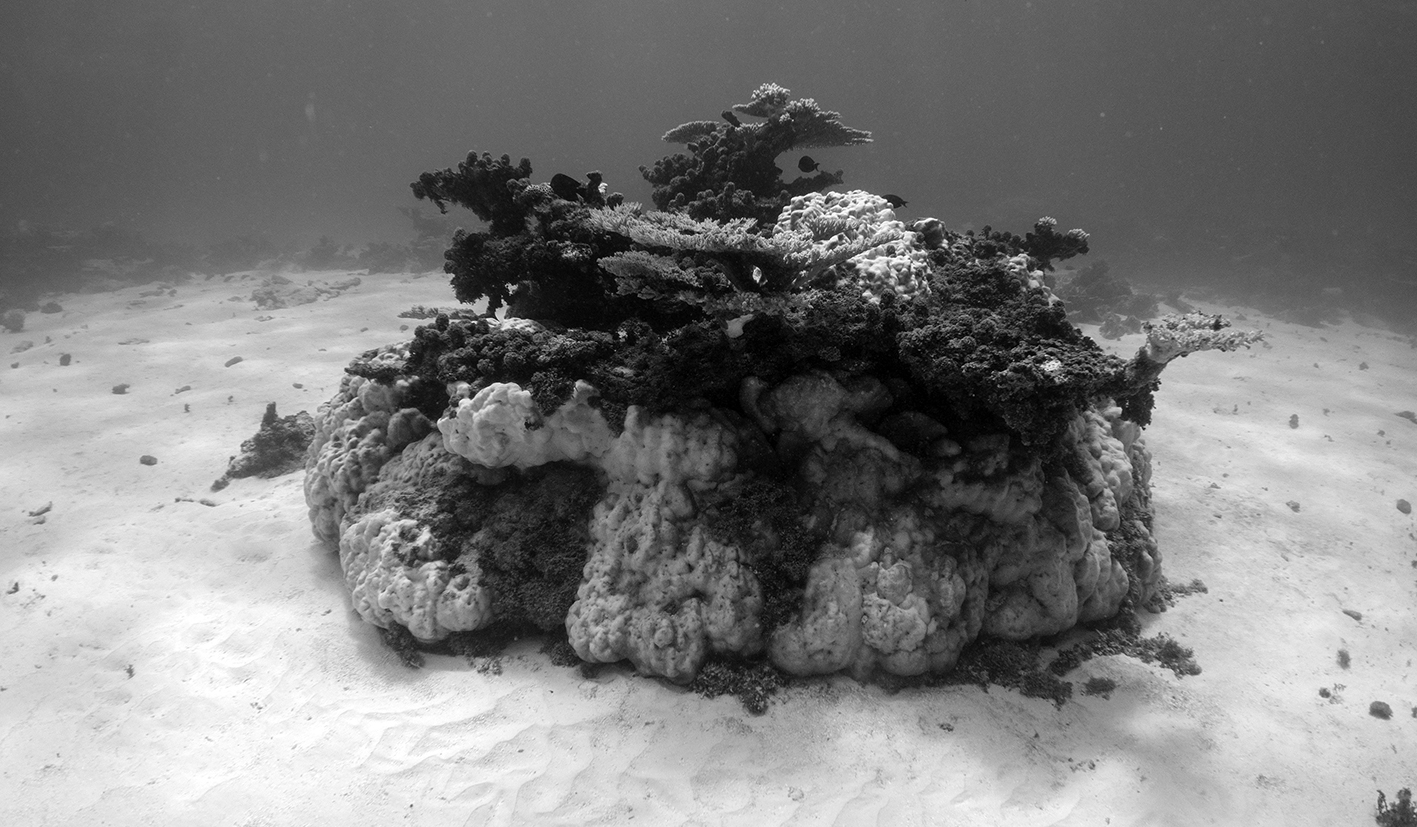

Pas la peine de sortir les bouteilles de plongée, tout se passe entre 0 et 5 mètres, je peux tout photographier en apnée. Jurriaan donne l’échelle d’une colonie gigantesque (Porites sp. ?) / No need to get out the scuba tanks, everything that is to be seen lies between 0 and 5 meters, I can photograph everything while freediving. Jurriaan gives the scale of a gigantic colony (Porites sp.?)

Une colonie d’Acropora ramifiée poussant sur une autre, tabulaire. / A branched Acropora colony growing on another, tabular one.

Parfois, les photos en noir-et-blanc accentuent le caractère mystérieux du monde sous-marin. / Sometimes black and white photos enhance the mysterious character of the underwater world.

Beaucoup de méduses Aurelia aurita, évoluent juste sous la surface. / Many Aurelia aurita jellyfish float just below the surface.

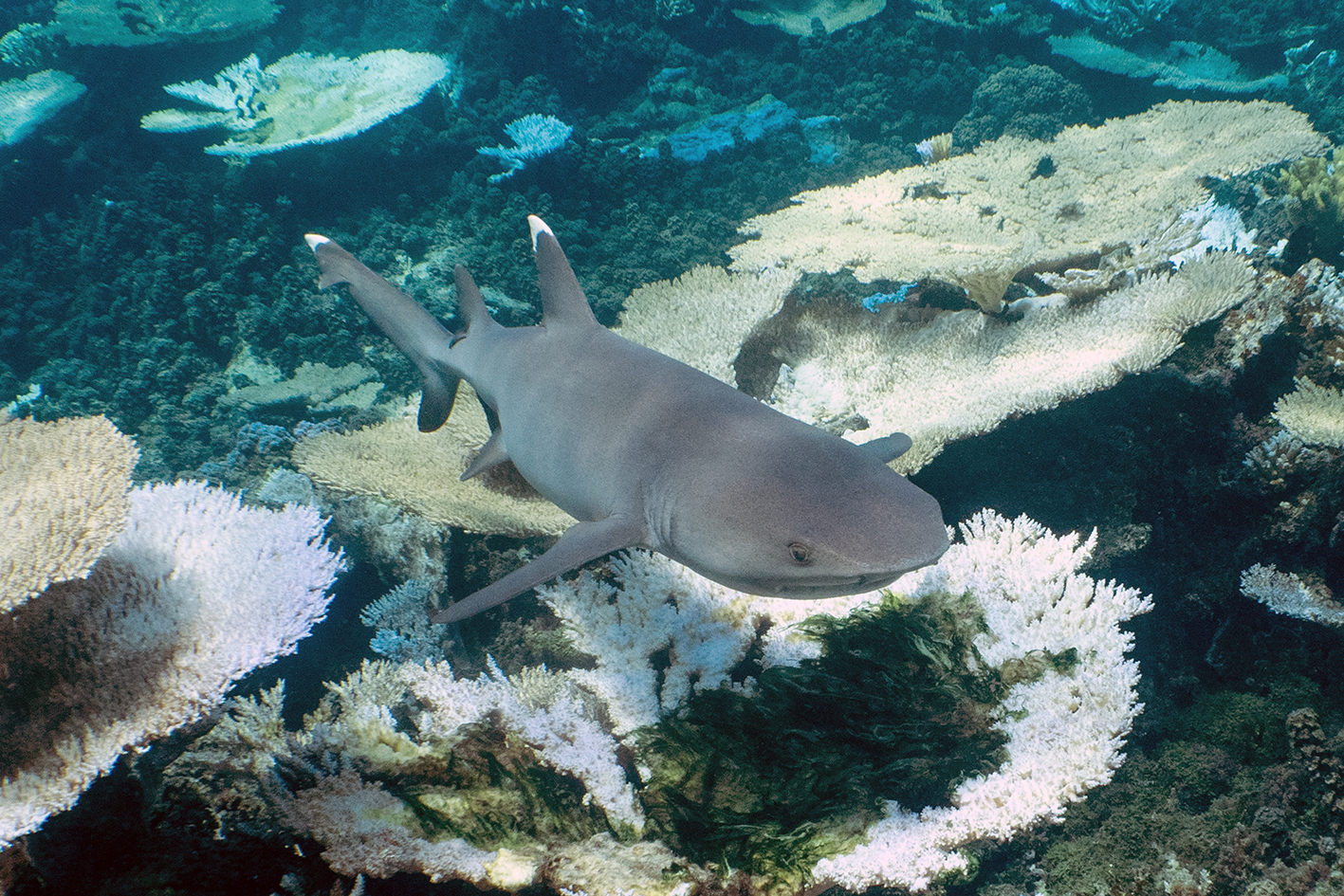

Puis on a un autre visiteur, un requin pointe blanche de récif (Triaenodon obesus) de grande taille, adulte. / Then we have another visitor, a large, adult whitetip reef shark (Triaenodon obesus).

Il est bien curieux et reste avec nous pendant un bon moment. / It is very curious and stays with us for a while.

Puis nous allons à terre, pour visiter l’église Saint-Gabriel de Taravai, construite en 1868, quand Taravai comptait plus de 2000 habitants. Aujourd’hui, seulement 8 de personnes vivent dans l’île, et la plupart ne fréquentent pas l’église. Cependant, on a commencé récemment à rénover l’édifice, travaux encore en cours. / Then we go ashore to visit the Church of St. Gabriel of Taravai, built in 1868, when Taravai had over 2,000 inhabitants. Today, only 8 people live on the island, and most do not attend church. However, renovations to the building have recently begun, and work is still ongoing.

Un couple habitant l’île, Valérie (Tahitienne) et Hervé (Mangarévien), vit de leurs récoltes, leurs poules, la chasse aux chèvres et cochons sauvages et leur pêche. Un dimanche sur deux, ils reçoivent les plaisanciers pour un barbecue convivial. / A couple living on the island, Valérie (Tahitian) and Hervé (Mangarevian), make a living from their crops, their chickens, hunting wild goats and pigs, and fishing. Every other Sunday, they welcome boaters for a friendly barbecue.

J’y rencontre, pour la 3ème fois, la Suissesse Gabriela, ancienne collègue de mon ami Stefan. Que le monde est petit ! / There I met, for the third time, Gabriela, a Swiss lady and former colleague of my friend Stefan. What a small world!

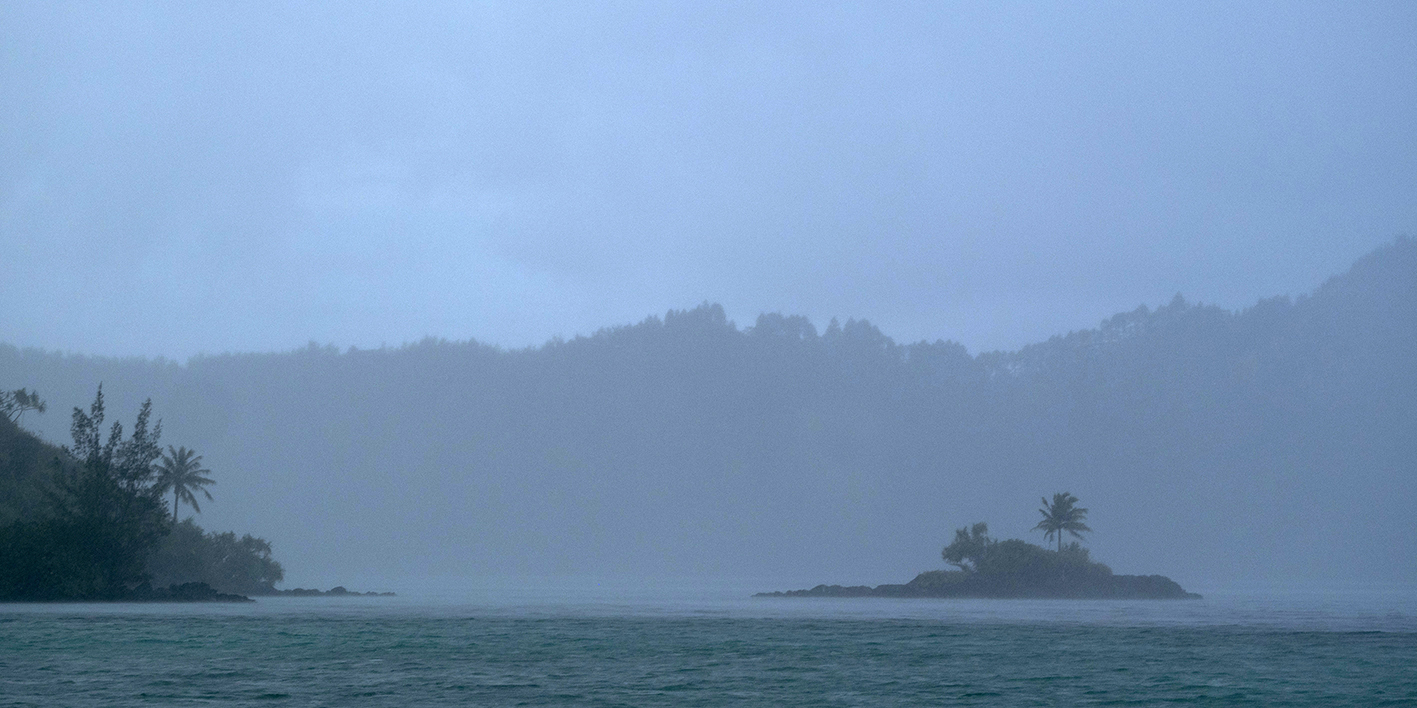

Mais le temps se gâte ! La Polynésie ne connaît pas toujours un ciel bleu. Le ciel menaçant se mue en une pluie torrentielle qui s’abat bientôt sur nous, interrompant ainsi la partie de volley des uns, celle de pétanque à laquelle je participe. / But the weather is turning bad! Polynesia doesn’t always have blue skies. The threatening sky turns into torrential rain that soon falls on us, interrupting the volleyball game some were playing, and the pétanque game I participated in.

Il est temps de rentrer sur Rikitea, car Christopher debit aller à l’école demain. Contre toute attente, pendant la traversée la météo s’arrange et la silhouette du mont Duff de Mangareva se découpe sur un beau coucher de soleil. / It’s time to head back to Rikitea, as Christopher has to attend school tomorrow. Against all expectations, the weather improves during the crossing, and the silhouette of Mount Duff of Mangareva is outlined against a beautiful sunset.

Samedi 15 mars 2025 / Saturday 15 March 2025

Après le petit-déjeuner, nous débarquons sur une plage déserte de l’île de Taravai. Vue sur Akamaru au fond et Agakauitai à droite. / After breakfast, we disembark on a deserted beach on Taravai Island. Views of Akamaru in the background and Agakauitai to the right.

Le petit explorateur Christopher part à la conquête de Taravai. / Little explorer Christopher sets out to conquer Taravai.

La plage de sable est bordée de pierres basaltiques, révélant la nature volcanique de l’archipel. / The sandy beach is lined with basalt stones, revealing the volcanic nature of the archipelago.

La plage est truffée de centaines de terriers de crabes-fantôme. / The beach is dotted with hundreds of ghost crab burrows.

La plupart se sont cachés à notre approche. Mais il y en a un, trop occupé à dévorer une guêpe, qui se fiche du photographe et me laisse l’approcher… / Most of them hid as we approached. But one, too busy devouring a wasp, ignored the photographer and let me approach him…

L’hibiscus des plages (Talipariti tiliaceum) possède des fleurs jaunes qui virent à l’orange en se fanant. Les fruits ressemblent à des petites pommes. / The beach hibiscus (Talipariti tiliaceum) has yellow flowers that turn orange as they fade. The fruits resemble small apples.

L’Ipomée pied-de-chèvre (Ipomoea pes-caprae) est une liane qui rampe sur le sable et produit des fleurs mauves. / Beach morning glory (Ipomoea pes-caprae) is a vine that creeps on sand and produces mauve flowers.

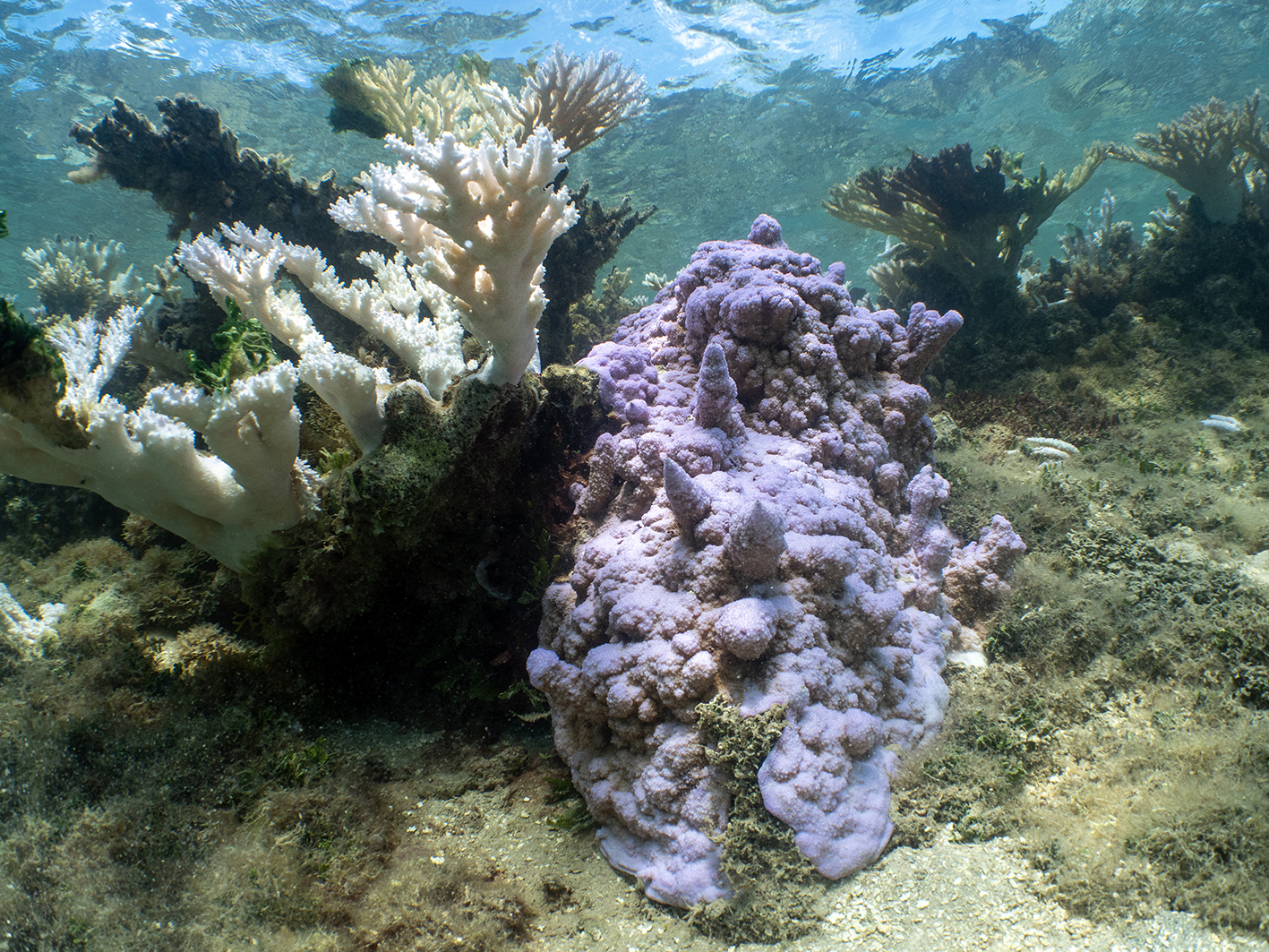

Après cette excursion terrestre, Jurriaan et moi partons à la découverte du récif. La visibilité est toujours aussi médiocre (environ 5 à 7 mètres), mais cette fois-ci je me suis équipé de mon boîtier sous-marin équipé d’un objectif grand-angle, ce qui me permet de faire de la photo en de bonnes conditions. Le récif frangeant se trouve entre la surface et environ 1m50 de profondeur. Au-delà, plus de coraux. Nous décidons donc de ne pas plonger en bouteille, ce qui me permet de renouer avec les joies de l’aplée ! Beaucoup d’acropores ramifiés montrent des signes de blanchissement… / After this land excursion, Jurriaan and I set off to explore the reef. Visibility is still poor (around 5 to 7 meters), but this time I’ve taken my underwater housing with a wide-angle lens, which allows me to take photos in good conditions. The fringing reef is located between the surface and around 1.5 meters deep. Beyond that, there are no more corals. We therefore decide not to scuba dive, which allows me to rediscover the joys of freediving! Many of the branched acropora are showing signs of bleaching…

D’autres, en revanche, semblent en bonne santé. / Others, on the other hand, appear to be in good health.

Acropores et porites (peut-être…). / Acropora and Porites (maybe…)

Coraux-champignon (Famille Fungiidae), consistant d’un seul polype géant. / Mushroom corals (Family Fungiidae), consisting of a single giant polyp.

Les coraux ramifiés peuvent servir d’abri à des petits poissons comme les demoiselles bleu-vert (Chromis viridis) et les demoiselles à trois bandes noires (Dascyllus aruanus). / Branching corals can provide shelter for small fish such as blue-green damselfish (Chromis viridis) and three-banded damselfish (Dascyllus aruanus).

Cet acropore abrite également des demoiselles à trois bandes noires (Dascyllus aruanus) et des sergeants-major (Abudefduf sexfasciatus) juvéniles. / This acropora also shelters juvenile three-banded damselflies (Dascyllus aruanus) and sergeant-majors (Abudefduf sexfasciatus).

Il y a pas mal de poissons, mais la plupart ne se laissent pas approcher facilement. Cette photo d’un poisson-perroquet capitaine (Chlorurus enneacanthus) est un coup de chance (et une longue apnée…) ! / There are quite a few fish, but most of them aren’t easy to approach. This photo of a captain parrotfish (Chlorurus enneacanthus) is a stroke of luck (and a long breath-hold…)!

Le temps a été très changeant toute la journée : soleil, ciel couvert, pluie… Mais cela se termine en un feu d’artifice vertigineux, tout en sirotant notre apéro ! / The weather was very changeable all day: sun, overcast skies, rain… But it ended in a dizzying fireworks display, while we sipped our aperitif!

Interview Bruno Schmidt

Quelqu’un m’avait expliqué où trouver le vieil homme : « Après le collège, après le terrain de sports, à gauche, une maison près de la mer. » Dès que je pénètre dans sa propriété – gazon ombragé par des arbres – il s’avance vers moi. Corps bronzé, musclé. De longs cheveux blancs dépassent de sa casquette. 90 ans ? On lui donnerait facilement vingt de moins ! Nous nous installons sur un tronc d’arbre, face à la mer. / Someone had told me where to find the old man: « Beyond the school, beyond the sports field, on the left, a house near the sea. » As soon as I enter his property—a lawn shaded by trees—he walks toward me. Tanned, muscular. Long white hair sticks out from under his cap. 90 years old? He could easily be twenty years younger! We sit down on a tree trunk, facing the sea.

« Je suis né à Mangareva en 1934, mais je ne suis pas un Mangarévéen de souche. Mon grand-père était allemand né au Danemark. Il a quitté l’Europe et a rencontré ma grand-mère chilienne à Valparaiso. Tout en bourlinguant, il a bossé à l’île de Pâques, puis à Mururoa. C’était bien avant les essais nucléaires : on y exploitait le coprah. Grand-père était contremaître dans une exploitation agricole. Puis il s’est installé à Mangareva. Mon père est né ici, et a épousé une Tahitienne qui vivait déjà dans l’île. / “I was born in Mangareva in 1934, but I’m not a native Mangarevean. My grandfather was German, born in Denmark. He left Europe and met my Chilean grandmother in Valparaiso. While traveling, he worked on Easter Island, then in Mururoa. This was long before the nuclear tests: copra was mined there. Grandfather was a foreman on a farm. Then he settled in Mangareva. My father was born here and married a Tahitian woman who already lived on the island.

Étant naturalisé français, comme tous les mineurs en Polynésie, mon père a été appelé sous les armes en 14-18. Il était infirmier dans les tranchées. De la Seconde Guerre mondiale je ne garde pas beaucoup de souvenirs. Il y avait moins d’approvisionnements, mais nous n’avions pas faim. Pour avoir de la lumière, nous utilisions la noix de bangoul. Cela produit beaucoup de suie. À propos, cette même suie était jadis utilisée pour les tatouages traditionnels. / Being a naturalized French citizen, like all those under-age in Polynesia, my father was called up for military service in 1914-1918. He was a medic in the trenches. I don’t have many memories of the Second World War. There were fewer supplies, but we weren’t hungry. To have light, we used the bangoul nut. It produces a lot of soot. By the way, this same soot was once used for traditional tattoos.

Dans ma jeunesse, la vie de l’île était rythmée par l’arrivée des bateaux qui venaient chercher le café, le coprah et la nacre. / In my youth, life on the island was punctuated by the arrival of boats that came to collect coffee, copra and mother-of-pearl.

J’ai fait mes études à Tahiti, et à l’âge de 19 ans, j’ai commencé à travailler. Quand le CEP s’est installé au début des années 1960, j’étais infirmier. On m’a chargé de récolter des échantillons de nourriture que je devais enfermer dans des sachets en plastique, même déjà pourris. Bien entendu, on ne m’a fourni aucune explication sur le but de la chose. » / I studied in Tahiti, and at the age of 19, I started working. When the CEP was established in the early 1960s, I was a nurse. I was tasked with collecting food samples that I had to seal in plastic bags, even if they were already rotten. Of course, I was given no explanation as to the purpose of this.”

Je lui demande ce qu’il pense du fait que la culture mangarévéenne ait disparu avec l’arrivée du catholicisme dans l’île. / I ask him what he thinks about the fact that Mangarevean culture disappeared with the arrival of Catholicism on the island.

« Lorsqu’en 1834, les pères François Caret et Honoré Laval sont arrivés sur l’île d’Akamaru, l’oncle du roi Maputeoa, Matua, les aida à apprendre la langue mangareva. Les Mangarévéens, contrairement aux Marquisiens plus guerriers, ne résistèrent pas longtemps à la conversion au catholicisme. Matua, qui était grand-prêtre, avait une influence bien plus grande que son cousin le roi, et lorsque Matua se convertit,Maputeoa lui-même suivait et se fit baptiser en 1836 en prenant le nom de « Grégoire » en l’honneur du pape de l’époque. La mission prospéra. Les maraes (lieux sacrés) furent détruits et des chapelles furent érigés sur les sites. Les habitants qui vivaient nus pour la plupart, reçurent des vêtements et des tissus. / “When Fathers François Caret and Honoré Laval arrived on the island of Akamaru in 1834, King Maputeoa’s uncle, Matua, helped them learn the Mangareva language. The Mangarevans, unlike the more warlike Marquesans, did not long resist conversion to Catholicism. Matua, who was a high priest, had far greater influence than his cousin the king, and when Matua converted, Maputeoa himself followed suit and was baptized in 1836, taking the name “Gregory” in honor of the pope at the time. The mission prospered. The maraes (sacred places) were destroyed and chapels were erected on the sites. The inhabitants, who mostly lived naked, were given clothes and fabrics.

On a dit beaucoup de mal des prêtres, mais ce sont surtout les commerçants de nacre européens qui les voyaient d’un mauvais œil, car les missionnaires régulaient la vente de nacre, afin d’éviter que les pêcheurs indigènes se fassent avoir. » / Much bad has been said about the priests, but it was mainly the European mother-of-pearl traders who looked down on them, because the missionaries regulated the sale of mother-of-pearl in order to prevent the native fishermen from being taken advantage of.

Je lui dis qu’avant de venir ici, j’avais lu le livre “L’Île d’Agnès – Itinéraire d’un Breton du 19ème siècle en Polynésie”, écrit par Jacques Guillou, qui vécut ici et qui avait épousé une Mangarévéenne. Le manuscrit de ce récit avait été découvert par un certain Jacques Sauvage. Mon interlocuteur rigole : / I told him that before coming here, I had read the book “L’Île d’Agnès – Itinéraire d’un Breton du 19ème siècle en Polynésie” (“The Island of Agnes – Itinerary of a 19th Century Breton in Polynesia”) written by Jacques Guillou, who lived here and married a Mangarévéan woman. The manuscript of this story had been discovered by a certain Jacques Sauvage. My interlocutor laughs:

« J’ai le même livre dans ma bibliothèque, avec une dédicace de Sauvage, que j’ai connu personnellement. Mais tout ce récit est du pipeau. Il n’y jamais eu de récit de ce Guilloux, bien qu’il ait vraiment existé. C’est Sauvage, s’inspirant largement des écrits du Père Laval, qui a inventé cette histoire de toutes pièces ! N’empêche que les données historiques de ce livre sont bien réelles, si on fait abstraction du prétendu vécu de ce Guilloux, qui était un simple déserteur venu vivre loin de la métropole ! » / « I have the same book in my library, with a dedication from Sauvage, whom I knew personally. But this whole story is a hoax. There has never been an account of this Guilloux, although he really existed. It was Sauvage, drawing largely on the writings of Father Laval, who invented this story from scratch! Nevertheless, the historical data in this book are very real, if we ignore the supposed life of this Guilloux, who was a simple deserter who came to live far from the metropolis! »

Il se tait, le regard perdu vers l’horizon. / He is silent, his gaze lost towards the horizon.

« Pour en revenir à la culture mangarévéenne, elle s’est effectivement perdue au fil du temps. Mais aujourd’hui, les jeunes se posent des questions et sont à la recherche de leurs origines. Les chants, les danses de jadis reviennent, on est plus attaché au mangarévéen qu’au français. Les jeunes cherchent des motifs décoratifs mangarévéens pour se les faire tatouer. Mon petit-fils Stéphane en fait partie. » / « As to Mangarevean culture, it has indeed been lost over time. But today, young people are asking questions and searching for their origins. The songs and dances of yesteryear are making a comeback; we are more attached to Mangarevean than to French. Young people are looking for Mangarevean decorative motifs to get tattooed. My grandson Stéphane is amongst them. »

Il se tait. Je prends congé de cet homme chaleureux, si incroyablement jeune de corps et d’esprit. / He falls silent. I take my leave of this warm man, so incredibly young in body and mind.

Vendredi 14 mars 2025 / Friday 14 March 2025

Ceux qui me connaissent doivent se dire : « Steven en Polynésie ? Il doit faire plein de photos sous-marines ! » Au risque de vous décevoir (et je suis un peu déçu moi-même de ce côté-là), jusqu’à présent pas de photos sous l’eau dignes de ce nom. À cela, plusieurs raisons. D’abord, on a beaucoup de vent, et la mer est plutôt agitée. Avec cela, partout où nous allons, la visibilité est plutôt mauvaise, l’eau étant troublée pour une raison que j’ignore. Du plancton ? Pas une seule plongée en dix jours sur place. Tout juste quelques petites balades en snorkeling, avec mon iPhone dans un boîtier étanche pas très maniable, avec lequel je fais quelques photos plutôt au jugé que de voir vraiment ce que je fais… Ne vous étonnez donc pas de la piètre qualité… Mais voici tout de même quelques images faites ce matin. Beaucoup de méduses aurélies : / Those who know me must be thinking: « Steven in Polynesia? He must be taking lots of underwater photos! » I might be disappointing you (and I’m a little disappointed myself on this score), so far I haven’t taken any decent underwater photos. There are several reasons for this. First, we have a lot of wind, and the sea is rather rough. With that, everywhere we go, visibility is rather poor, the water being cloudy for some reason I don’t know. Plankton? Not a single dive in ten days here. Just a few short snorkeling trips, with my iPhone in a waterproof case that’s not very handy, with which I take a few photos rather by guesswork than really seeing what I’m doing… So don’t be surprised by the poor quality… But here are a few images taken this morning. Lots of jellyfish:

Des demi-becs évoluant juste sous la surface. / Half-beaks evolving just below the surface.

Des sergents-major parmi les branches d’acropore. / Sergeant-majors among the branches of acropora.

Passage d’un petit requin pointe-blanche de récif. / A small white-tip reef-shark passes by.

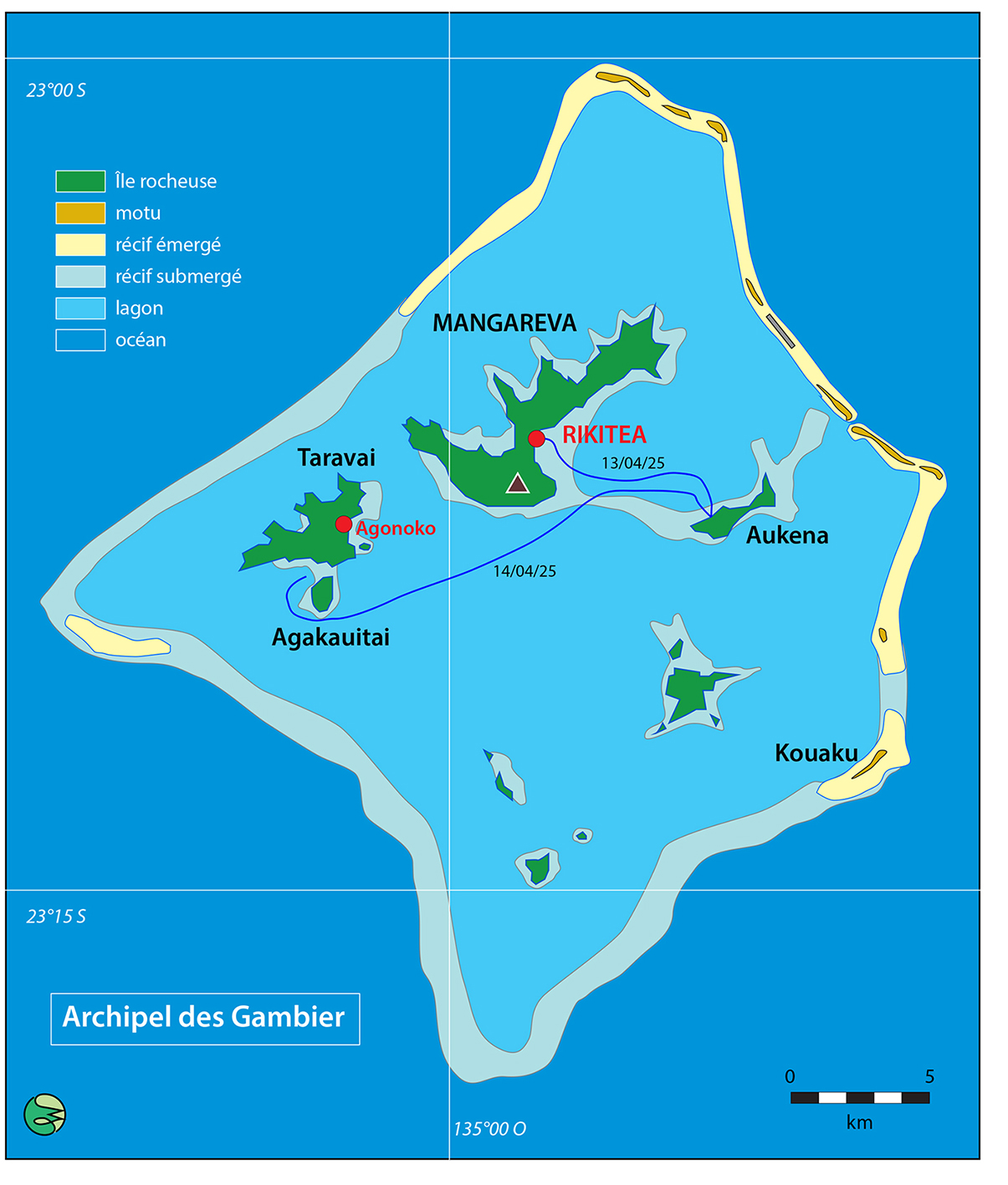

Hier, nous avions traversé de Mangareva à Aukena, aujourd’hui navigation d’Aukena à Agakauitai. / Yesterday we crossed from Mangareva to Aukena, today we sail from Aukena to Agakauitai.

Dans les deux cas, j’ai fait le guet, pour prévenir Jurriaan des multiples bouées de perliculteurs qui rendent la navigation difficile. [Photo Camila De Conto] / In both cases, I kept watch, to warn Jurriaan of the many pearl farmers’ buoys that make navigation difficult. [Photo Camila De Conto]

Le vent est fort, la mer agitée. Après seulement 3 mois d’utilisation, le pavillon luxembourgeois de « Songster » est déjà en lambeaux. Ceux qui ornaient les capots de « La Petite » et de « La Charmante » avaient mieux résisté aux intempéries ! / The wind is strong, the sea rough. After only 3 months of use, the Luxembourg flag of « Songster » is already in tatters. Those that adorned the hoods of « La Petite » and « La Charmante » had withstood the weather better!

Nous arrivons à l’île d’Agakauitai. Les vagues déferlent sur les rochers. / We arrive at Agakauitai Island. Waves crash against the rocks.

À gauche Taravai, à droite Agakauitai, et au fond, entre les deux, Mangareva. / On the left Taravai, on the right Agakauitai, and in the background, between the two, Mangareva.

Paysages idylliques. Les Gambier ne sont pas des îles plates coralliennes avec des palmiers, mais des îles volcaniques escarpées, avec une végétation diverse, dont beaucoup de pins. / Idyllic landscapes. The Gambier Islands are not flat coral islands with palm trees, but rugged volcanic islands with diverse vegetation, including many pine trees.

Petite excursion à terre : les 3 hommes de l’équipage. [Photo Camila De Conto] / Short excursion ashore: the 3 men of the crew. [Photo Camila De Conto]

Nid de guêpe dans un pin. / Wasp nest in a pine tree.

Fin d’une longue journée, suivie de la préparation des photos et de l’écriture du blog… Temps de me coucher ! / End of a long day, followed by preparing photos and writing the blog… Time to go to bed!

Jeudi 13 mars 2025 / Thursday 13 March 2025

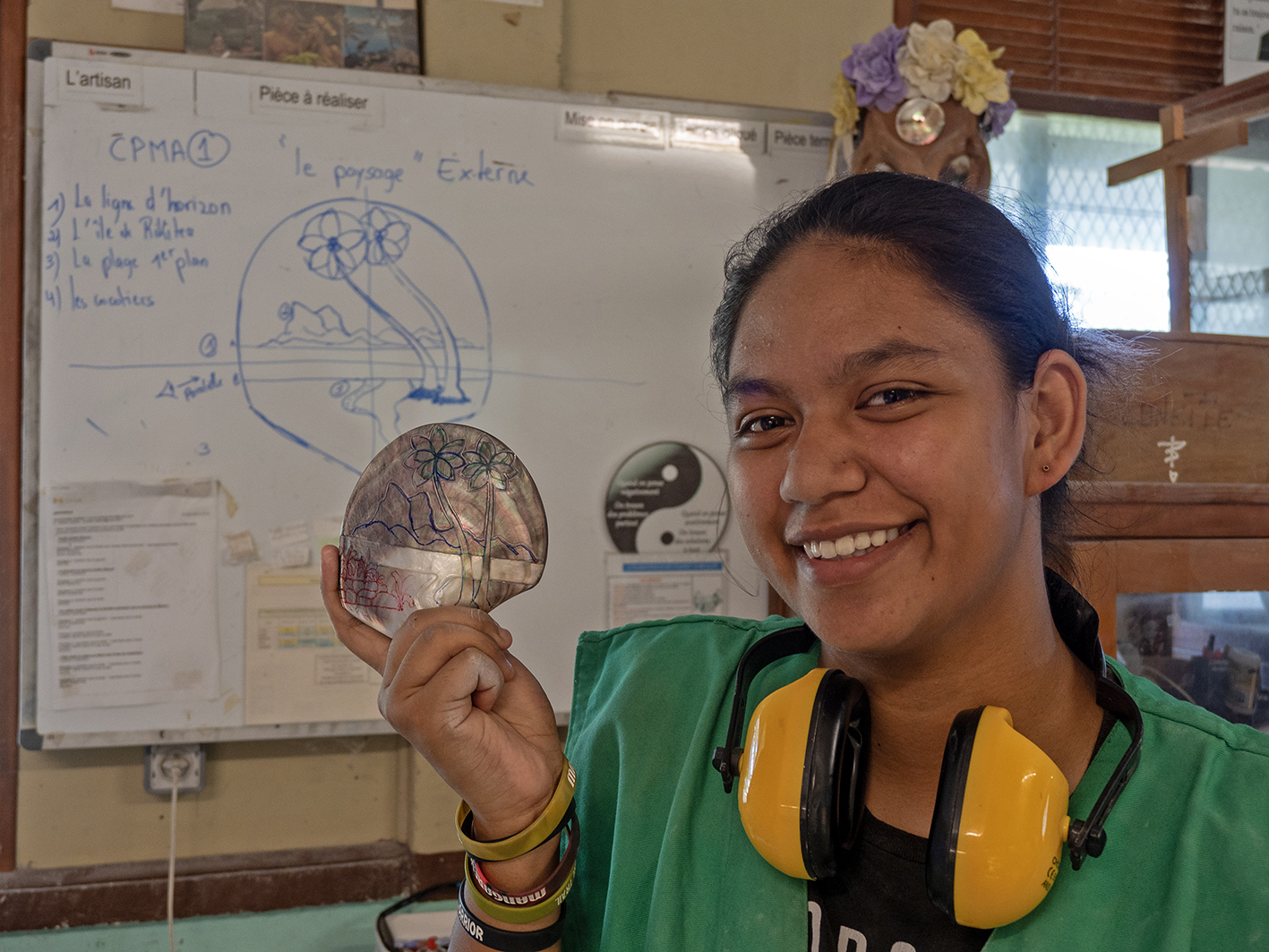

Nous nous rendons au College Saint Raphael de Rikitea, qui scolarise près de 150 jeunes répartis en deux grands blocs : le collège et la formation professionnelle. Cette dernière est surtout connue pour sa formation en gravure sur nacre. Ici, le jeune Marama au travail. La poussière de nacre résultant du travail de gravure est aspirée par le tuyau gris, mais malgré ça, les jeunes sont obligés de porter un masque ainsi qu’un casque pour protéger les oreilles du bruit. / We’re heading to the Saint Raphael College in Rikitea, which educates nearly 150 young people divided into two main blocks: middle school and vocational training. The latter is best known for its mother-of-pearl engraving program. Here, young Marama at work. The mother-of-pearl dust resulting from the engraving process is sucked up through the gray hose, but despite this, the youngsters are required to wear masks against the dust and headphones to protect their ears from the noise.

Mihi montre la coquille sur laquelle elle va graver d’après l’exemple se trouvant sur le tableau blanc. / Mihi shows the shell she is going to engrave based on the example on the whiteboard.

C’est un travail minutieux qui demande patience et adresse. / It is meticulous work that requires patience and skill.

Poevai montre un coquillage sur lequel elle a gravé un thème floral. / Poevai shows a shell on which she has engraved a floral theme.

Des médailles pour le taratutu (« parler d’une voix forte ») de 2025, avec la tour du roi Maputeoa. / Medals for the taratutu (“speaking with a loud voice”) from 2025, with the tower of King Maputeoa.

Avec l’arrivée des missionnaires et l’implantation du catholicisme il y a près de deux siècles, la culture mangarévienne a quasiment disparu. Mais récemment, la jeune génération est à la recherche de ses racines : on voit par exemple de plus en plus de tatouages avec des motifs mangaréviens. Ici des coquillages avec la représentation d’une statue et d’autres motifs religieux d’avant la christianisation. Sur le troisième, des thèmes linguistiques du « ki mangareva » (« le dire mangarévien ») : TOLA = femme, TAMAROA = homme, TOROMIKI = enfant. / With the arrival of the missionaries and the establishment of Catholicism nearly two centuries ago, Mangarevan culture virtually disappeared. But recently, the younger generation is searching for its roots: for example, we are seeing more and more tattoos with Mangarevan motifs. Here, shells with the representation of a statue and other religious motifs from before Christianization. On the third, linguistic themes of « ki mangareva » (« Mangarevian speech »): TOLA = woman, TAMAROA = man, TOROMIKI = child.

Poevai a tressé une couronne pour Camila. / Poevai braided a crown for Camila

On se rend chez un artisan qui fait des bijoux à base de perles. Il y en a de toutes les couleurs ! Lesquelles prendre pour Marie-Xavier ? Ne vous inquiétez pas : le choix est fait ! / We’re heading to a craftsman who makes pearl jewelry. They come in all sorts of colors! Which ones for Marie-Xavier? Don’t worry: the choice is made!

Dans l’après-midi, nous levons l’ancre afin de faire la traversée à l’île d’Aukéna. Il faut rester dans le chenal balisé afin de ne pas s’échouer sur le récif. Ensuite, c’est le parcours du combattant à travers les centaines de bouées qui marquent les parcs de perliculture. On dirait un champ de mines ! / In the afternoon, we weigh anchor to make the crossing to Aukéna Island. We must stay within the marked channel to avoid running aground on the reef. Then, it’s an obstacle course through the hundreds of buoys marking the pearl farms. It’s like a minefield!

Nous voici arrivés à Aukéna. / Here we are at Aukéna.

La toute première église de la Polynésie était construite à Aukéna. Elle est dédiée à Saint Raphaël archange. Au départ, elle est en bois. Les constructions en dur se réalisent après, notamment grâce au frère Gilbert Soulié, venu rejoindre la mission en mai 1835. / The very first church in Polynesia was built in Aukéna. It is dedicated to Saint Raphael the Archangel. Initially, it was made of wood. Permanent structures were later built, notably thanks to Brother Gilbert Soulié, who joined the mission in May 1835.

Nous rencontrons Anton Paroi. C’est lui qui détient la clef de la chapelle, où il va prier tous les matins. Avec son voisin qui habite à des kilomètres d’ici, ils sont les seuls habitants de l’île ! / We meet Anton Paroi. He holds the key to the chapel, where he prays every morning. Along with his neighbor who lives miles away, they are the only inhabitants of the island!

Nous regagnons « Songster », qui se découpe sur un beau ciel, avec Mangareva en arrière-plan. / We return to “Songster”, which stands out against a beautiful sky, with Mangareva in the background.

Le soleil se couche. Cette nuit, nous allons assister à un spectacle unique : nous aurons droit à une éclipse lunaire totale ! / The sun is setting. Tonight, we’re in for a unique spectacle: a total lunar eclipse!

Mercredi 12 mars 2025 / Wednesday 12 March 2025

Interview de Caroline Mamatui

Lorsque j’arrive à sa petite maison coquette qui se trouve juste derrière la cathédrale Saint-Michel, elle est en train d’arroser son jardin. Portant des lunettes foncées (« Je viens d’être opérée des yeux »), ses cheveux blancs tranchent sur sa peau mate. Elle m’invite à m’asseoir.

« Je suis née ici en 1945. Nous étions six : 2 frères et 4 sœurs. Enfant, j’étais en très mauvaise santé. Lorsque ma famille a déménagé à Tahiti pour y trouver du travail, j’ai été adoptée par un couple sans enfant. Mes nouveaux parents étaient très pauvres. À l’époque de ma jeunesse, il y avait encore la culture du coprah et du café dans l’île. Mon père y travaillait, ou alors il allait plonger pour ramener de la nacre. La plupart des plongeurs étaient des hommes, mais il y avait quelques femmes élgalement. Pour assurer la pérennité de la récolte, le lagon était divisé en quatre secteurs. Il y avait une rotation annuelle. On exploitait un seul secteur par an, laissant les trois autres en friche.

J’accompagnais parfois mon père en mer sur sa pirogue. Il plongeait avec un plomb attaché à une corde et avec des petites lunettes pour voir sous l’eau. Lorsqu’il fallait le remonter, il secouait la corde et je devais alors tirer dessus, pour le remonter avec sa gueuse de plomb. Les plus belles coquilles à nacre se trouvaient également les plus profonds. Je me souviens que je pleurais quand mon père allait plonger dans la passe, très profonde. Il n’y avait personne d’autre et j’avais très peur qu’il ne remonterait pas. »

L’arrivée de la bombe atomique

« À l’époque de ma jeunesse, on vivait en communautés par quartier. Il y avait beaucoup d’entraide, pour travailler la terre, reconstruire une maison… On partageait la nourriture, surtout les poissons pêchés dans le lagon, car on n’avait pas encore de frigos.

En 1963, notre vie a changé, avec l’arrivée d’un premier régiment de militaires dans le district de Taku, la construction d’une route et l’installation d’une station météorologique au col. Puis ils s’installèrent également sur le motu de Totegegie. Ils étaient 700 militaires pour seulement 500 locaux. Ils ont construit des bunkers. Bien entendu, nous, pauvres Mangaréviens, n’étions au courant de rien !

Je me suis retrouvée enceinte à deux reprises. Les pères de mes deux fils sont repartis sans laisser de trace. Lorsqu’en 1966 a eu lieu le premier tir nucléaire à Mururoa, on nous a obligés d’entrer dans un abri. J’avais 21 ans et j’étais enceinte de huit mois. Nous n’y sommes restés qu’une seule nuit. Je me souviens d’avoir senti les vibrations de la détonation, mais bien sûr nous ne savions pas ce qui se passait.

Mais les essais atomiques ont totalement changé la vie des Mangaréviens. On nous incitait à planter des légumes, qui étaient destinés aux militaires à Mururoa. Régulièrement, des bateaux venaient les chercher. Comme cela nous a assuré des revenus, les gens pouvaient faire venir des matériaux pour construire en dur. Ma maison [elle fait un geste autour d’elle] est celle qu’ont construite mes parents à l’époque. Elle a soixante ans. En 1968, les militaires ont quitté les îles Gambier. »

L’amour de Dieu

« Plus tard, je suis devenue laïque consacrée, m’occupant, en dehors de la prière, de la catéchèse et de la préparation des personnes qui le désirent à l’entrée dans l’Église. Je prie pour ceux qui sont en mer, en l’air et sur les autoroutes, pour qu’ils arrivent à bon port. » [Puis, d’une voix forte et tournant le visage vers le ciel :] « Dieu, je Vous aime, je Vous adore ! Je sais que Tu es là. » [et, se tournant vers moi :] « Dieu nous a créé, Dieu a tout fait. Il est éternel, Il est le plus grand. Je ne doute jamais, et je ne vais pas me mettre à douter à 80 ans ! »

[Lorsque je lui demande ce qu’elle pense de l’arrivée des missionnaires, vers 1830, et de la disparition des croyances locales au profit de la religion catholique :]

« Je pense que la transition de la religion païenne polythéiste vers le catholicisme a été un mieux. De surcroît, les Pères ont défendu la population locale contre les mauvaises pratiques des commerçants européens, qui échangeaient des barriques entières de nacres contre un simple canif ! »

La même nacre qui décore maintenant l’intérieur de la cathédrale. Je prends congé de Caroline. Il est temps pour elle d’aller prier.Caroline Mamatui (12/03/25)

•••

Interview of Caroline Mamatui

When I arrive at her charming little house just behind Saint-Michel Cathedral, she is watering her garden. Wearing dark glasses (« I just had eye surgery »), her white hair contrasts with her olive skin. She invites me to sit down.

« I was born here in 1945. There were six of us: two brothers and four sisters. As a child, I was in very poor health. When my family moved to Tahiti to find work, I was adopted by a childless couple. My new parents were very poor. When I was growing up, copra and coffee were still being grown on the island. My father worked there, or he went diving to collect mother-of-pearl. Most of the divers were men, but there were also a few women. To ensure the sustainability of the harvest, the lagoon was divided into four sectors. There was an annual rotation. We only exploited one sector per year, leaving the other three fallow.

I sometimes accompanied my father to the sea in his canoe. He dived with a lead weight attached to a rope and with small goggles to see underwater. When we had to haul him in, he jerked the rope, and I had to pull on it to bring him up with his lead weight. The most beautiful mother-of-pearl shells were also found in the deepest areas. I remember crying when my father went to dive into the channel, which was very deep. There was no one else there, and I was very afraid he wouldn’t come back up.”

The Arrival of the Atomic Bomb

« When I was growing up, we lived in neighbourhood communities. There was a lot of mutual help, working the land, rebuilding a house… We shared food, especially fish caught in the lagoon, because we didn’t yet have refrigerators.

In 1963, our lives changed with the arrival of the first military regiment in the Taku district, the construction of a road, and the installation of a weather station at the pass. Then they also settled on the motu of Totegegie. There were 700 soldiers for only 500 locals. They built bunkers. Of course, we poor Mangarevans didn’t understand!

I became pregnant twice. The fathers of my two sons left without a trace. When the first nuclear test took place in Mururoa in 1966, we were forced into a shelter. I was 21 years old and eight months pregnant. We only stayed there for one night. I remember feeling the vibrations of the detonation, but of course, we didn’t know what was happening.

But the atomic tests completely changed the lives of the Mangarevans. We were encouraged to plant vegetables, which were intended for the military in Mururoa. Boats regularly came to collect them. Since this provided us with an income, people could bring in materials to build a permanent home. My house [she gestures around her] is the one my parents built at the time. It’s sixty years old. In 1968, the military left the Gambier Islands.”

God’s Love

« Later, I became a consecrated lay person, working, apart from prayer, on catechesis and preparing those who wish to enter the Church. I pray for those at sea, in the air, and on the highways, that they may arrive safely. » [Then, in a loud voice and looking up to the sky:] « God, I love You, I adore You! I know You are there. » [and, turning to me:] « God created us, God made everything. He is eternal, He is the greatest. I never doubt, and I’m not going to start doubting at 80! »

[When I ask her what she thinks of the arrival of the missionaries, around 1830, and the disappearance of local beliefs in favour of the Catholic religion:] « I think the transition from the polytheistic pagan religion to Catholicism was for the better. Moreover, the Fathers defended the local population against the evil practices of European traders, who traded entire barrels of mother-of-pearl for a simple penknife! »

The same mother-of-pearl that now decorates the interior of the cathedral. I take my leave of Caroline. It’s time for her to go and pray.